Why do the Greeks want the “Elgin Marbles” back? How did the Parthenon Sculptures end up in Britain in the first place? Why did the UK Prime Minister “lost his marbles”?

A Diplomatic Row

In November 2023, the prime minister of the United Kingdom cancelled a long awaited meeting with his Greek counterpart, while the latter had already arrived in London. A move that raised many eyebrows, with King Charles, who has a Greek lineage through his father, reportedly being extremely dissatisfied with this diplomatic row.

One of the main topics of their discussion was going to be the return of Greek antiquities, widely known as the Parthenon Sculptures or Elgin Marbles, from the British Museum back to Athens. For more than 30 years, the Greek government has been requesting the collection of marble architectural decorations from the Acropolis of Athens, especially from the Parthenon and the nearby Erechtheion Temple, that somehow ended up in Great Britain approximately 200 years ago.

The questions are endless. How did the so-called Elgin row start? Who is Elgin and how did he get his hands on some of the most sacred monuments of Greece? Why does the British Museum refuse to give the marble sculptures back to the Greeks, even after the construction of the new Acropolis Museum?

Lord Elgin and His Quest

Once upon a time, when the world was ruled by aristocrats and the land of the Greeks was occupied by the Ottoman Empire, there was a British Earl named Thomas Bruce. The man was known as Lord Elgin, as he was the 7th Earl of the small town of Elgin, Scotland. Just like the other western noblemen of his time, Lord Elgin was fascinated with ancient Greece and specifically ancient Athens. It was the time when the Greek Revival and Neoclassicism movements flourished, a topic that has been covered in a separate article.

In the early 19th century, a British nobleman was sent to Constantinople to take over the role of the British ambassador in the Ottoman Empire. Elgin was now in proximity to a city that always intrigued him. That was no other than Athens, the birthplace of Democracy; a place known for its glorious Acropolis Hill, a citadel and sacred hill that was covered in marvelous temples made of Pentelic marble. That is when he decided that an artistic and architectural quest to the Acropolis Hill was necessary to draw and replicate the ancient wonders. Or at least, that is what he publicly said. His actual motive was revealed later by his own actions.

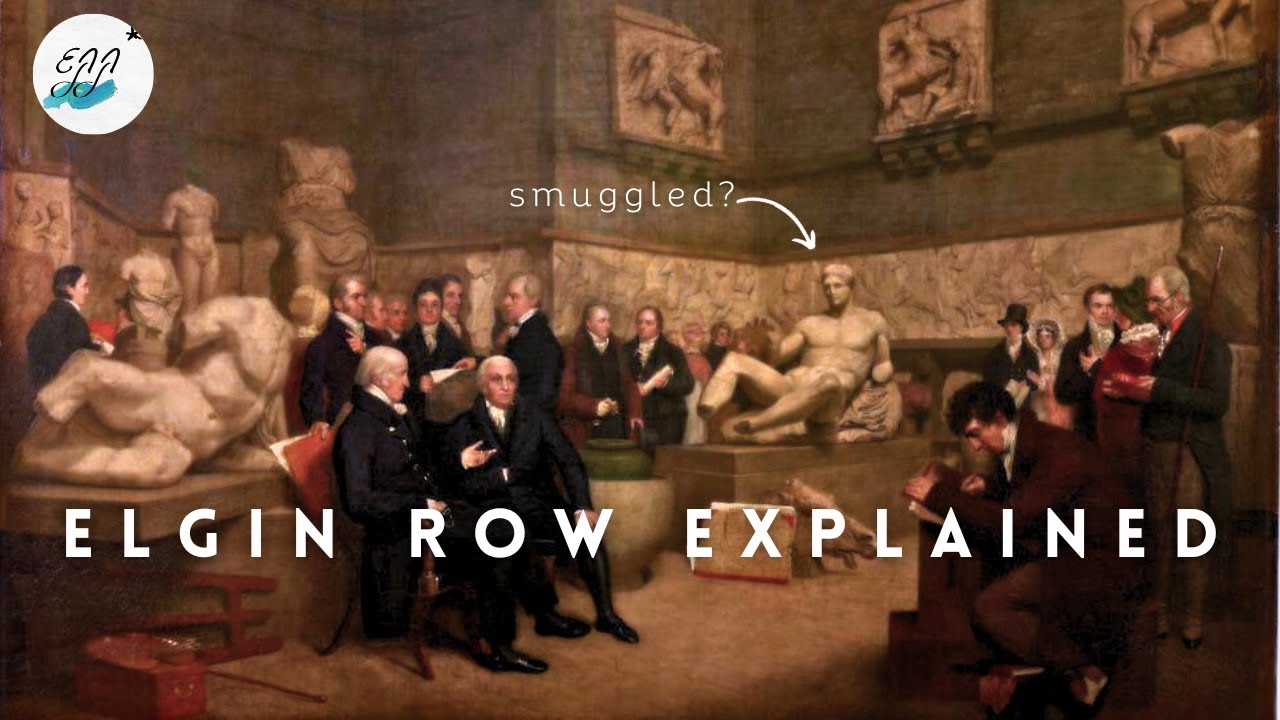

Together with the Italian painter Giovanni Batista Lusieri, known for his extremely realistic paintings, and several skillful craftsmen, he stormed the Acropolis Hill in the hot summer of 1800. A year later, things… escalated, when the decision to take fallen pieces of marble art and columns was made, with Elgin reportedly showing off a firman, as the Ottoman mandates were called, that supposedly allowed him to do so. However, he did not stay there. An English priest named Philip Hunt reportedly encouraged Lord Elgin to cut pieces out of the ancient Greek temples to showcase them in the United Kingdom. Many speculate that heavy bribing was involved to allow the Englishmen to basically steal the ancient artifacts, including half of the Parthenon’s frieze.

The original firman has not survived, and only an Italian translation exists that was made by the British Embassy in Constantinople and is now in the possession of the British Museum. The legal status of this document is debated. However, even if it is an official firman, three more questions arise.

Did the Ottomans really allow Elgin to actually cut pieces off the Parthenon and other temples, including an entire Caryatid sculpture that carried the roof of the Erectheion? If they did, how ethical or even legal was their displayed ownership over another nation’s historical treasures? Lastly, even if the whole process was approved by the rulers of that time, how is the act of cutting off pieces of ancient art in half and calling them “marbles”, only to display them abroad and make profit from them, cannot be considered criminal or at least of questionable morality?

The Parthenon Sculptures at the British Museum

Lord Elgin and his team lived at a time when ancient art collections were status symbols among British nobility. The collector was perceived as both rich and well-educated, with ancient Greek pieces being even more prestigious. Nobles saw ancient Athens as the pinnacle of morality, harmony, beauty, and perfection. They saw Greeks or Hellenes as a lost civilization and themselves as their continuation. They believed that the local population was annihilated after the Ottoman occupation, and it was their duty to keep the Greek spirit alive.

Elgin felt entitled to the Parthenon sculptures and could not wait to add many of the pieces in his art collection. However, he could simply not turn his mansions into Greek temples. There were so many findings and too little space. Moreover, the nobleman had found himself into debt. Profiting by selling parts of the Parthenon sculptures would get rid of his financial burdens.

The artifacts were stored into vessels that were set to reach Britain in 1803. However, the first vessel to disembark, the Mentor, sank with all its antiquities near the island of Kithira. Thankfully, most of the relics were recovered by divers three years later, while some were found recently.

The actions of Elgin dissatisfied a great number of philhellenes and art appraisers who interpreted them as vandalism. Lord Byron, the British poet and philhellene, dedicated a not-so-flattering poem to Elgin:

“Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!”

-Lord Byron

In 1810, Elgin attempted to defend his actions with a pamphlet, stating that he saved the artifacts from decay. Six years later, the translation of the firman he had reportedly acquired was shown to a British parliamentary committee, with its members deciding that the relics were legally acquired. Eventually, most of the Athenian artifacts reached Great Britain and parts of the collection were sold for 35.000 pounds to the British Museum, where they are still found to this day. The Museum also resolved the Lord’s financial problems and paid for the costs of his recent divorce.

The Elgin Row

A few years later, the Greeks, the people who many of the English noblemen considered extinct, revolted against the Ottoman Empire once again. This time, they were successful, and the modern Hellenic nation was born, with most of its lands freed from external forces. The ideals of ancient Greek antiquity and the legacy of the Byzantine Empire were at the forefront of the nation. Acropolis stood as a reminder of Greece’s glorious past and the damages it had withstood due to wars, natural catastrophes, and the recent “works” of Elgin, were apparent. Once the government had the capacity to store and safely display the works in a museum on the Acropolis Hill, requests to return the artifacts were made, which were snubbed in the beginning.

In 1963, a law called the British Museum Act was issued to prevent any removal of artifacts from the British Museum. Campaigns had already started years prior, featuring important Greek figures, including the international actress Melina Merkouri. In 1983, the Greek government made an official request for their permanent return, with Great Britain claiming that the country does not meet the safety requirements in its museums to preserve its own relics. Although the claim is questionable, with the British Museum reportedly causing the damage or even disappearance of thousands of Greek relics, with many objects suspected to be already sold in the black market, Greece constructed a state-of-the-art museum just for the Acropolis artifacts.

The safety concerns were now less believable, with the British Museum now saying that, not only they have the legal ownership of the Parthenon marbles, but that the latter belong to the world’s collective culture and that the museum has a “legal and moral responsibility to preserve and maintain all the collections in their care and to make them accessible to world audiences.” Which is an interesting claim given the fact that Greece will be displaying its relics at a museum that receives millions of visitors from around the world every year. The visitors, in this case, will be able to admire the collection in all its beauty. The work of art will be completed, as the marble metopes and decorative objects were meant to construct one piece of architectural wonder.

As the Greek prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, has recently stated before the cancellation of his meeting with his English counterpart, the Elgin row is more than an ownership problem. “Where can you best appreciate what is essentially one monument? It’s as if I had told you [I] had cut the Mona Lisa in half and you would have half of it at the Louvre and half of it at the British Museum.”

A War of Words

The Greek prime minister’s statement reportedly infuriated the other side. At the same time, it did change the mind of others, such as TV presenter Piers Morgan, who found the comparison quite compelling. In a way, the Elgin row is a war of words. The British side, for example, refers to the relics as the “Elgin marbles”. In this way, the ownership of Elgin over them is implied, while the word “marbles” diminishes the worth of these findings. Marble is the material from which these artworks were made. As a material, it can be cut in half and morphed into something else. From this perspective, why would the Greek nation care about the marbles of a British nobleman?

Not only that, but, the sentiment that the modern Greek nation has no moral or legal ownership over ancient Greek relics has been long established in specific parts of the world, through language. For example, by taking a look over old and recent British encyclopedias, you may notice that the Greeks are referred in past sense. As if they existed in a time that is long-lost, annihilated from the Earth like the dinosaurs. Mockumentaries implying the construction of the temples by aliens, further promote the alienation of the Greek citizens from their historical treasures.

It is important to note that other cultures are also requesting the return of their artifacts from the British and other Museums. Some fear that the return of the Greek artifacts can create a snowball effect, with other countries demanding immediate actions.

In A Nutshell:

- The Parthenon Sculptures are a collection of Greek artifacts displayed at the British Museum.

- The term is not limited to the temple of the Parthenon. It refers to a long list of artifacts from surrounding temples and even regions outside of Athens.

- The British Museum bought the collection from a British Earl known as Lord Elgin in the 19th Century.

- The legal ownership of the Parthenon Sculptures is disputed.

- Greece has been requested the reunification of the artifacts for years and contrustred a museum to display the artifacts.

- In November 2023, the UK PM refused to continue the talks for the return of the Greek relics with his Greek counterpart, causing a diplomatic row.

- King Charles and many British political and cultural figures support Greece’s request, with some expecting the reunification to occur within the next months.

- More countries are requesting the return of their lost relics.

What is your opinion regarding the so-called Elgin row? Should the Parthenon sculptures return to Greece?